No current cloud, commercial or military, lets frontline troops access both classified and unclassified data from all over the world, Dana Deasy told Breaking Defense. That makes JEDI unique – and too complex to split up among multiple contractors.

By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: A lot of people – even experts – don't get what the JEDI cloud computing program is really about, Dana Deasy told me. And that, the Defense Department's Chief Information Officer admitted, is partly the Pentagon's own fault he told me during a half-hour interview.

So, this morning, after Breaking Defense published the latest of several stories on JEDI's legal and political troubles and the mounting criticism of the program, Deasy agreed to an interview to explain just why he thinks the worldwide military cloud is still essential – and too complexly integrated to split chunks off to different contractors.

There are three fundamental misunderstandings about JEDI that the Pentagon needs to dispel, Deasy told me:

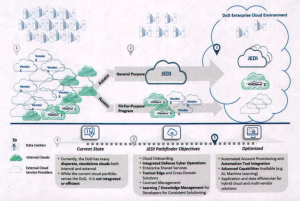

- First, people think JEDI is meant to be the one cloud to rule them all. It's not. While JEDI will be the default option for “general purpose” cloud computing across the entire Department of Defense, it will not replace hundreds of existing cloud contracts across the DoD not prevent the creation of new “fit for purpose” clouds tailored to specific missions.

“We definitely had created the wrong perception. People believed that we were going to take all of our clouds, get rid of them, and migrate everything over to JEDI,” Deasy told me. “That was clearly never the intent.”

- Second, people think JEDI is a 10-year, $10 billion contract. It's not – not necessarily. While that's the maximum value and duration of the contract, the Pentagon has the option to terminate it after two years. There's another end-it-or-extend-it decision three years later, and a third three years after that. The minimum the winning contractor is guaranteed to get? Just $1 million over two years.

The Defense Department's strategy to transition to cloud computing.

“When I came on board, one thing I did was restructure the terms,” Deasy told me. “I've been working with clouds since clouds were first brought to the commercial industry marketplace, and about every two to three years, you see really big changes. I'm talking about significant enough changes where you just want to step back and look at the marketplace. That's why we changed the terms of the contract.”

- Third, people think JEDI is just another cloud. It's not. While existing military and even civilian clouds can do some of what JEDI is meant to do, none of them can do all of it. None of them can pull unclassified, secret, and top secret data, from the Pentagon, bases around the world, and forward outposts, and put it all together in a way that even troops in combat can access.

- “Go out to the tactical edge, sit down with the warfighter, and look at how we push information out to someone who's literally outside of the village on the side of a mountain,” Deasy told me. “I spent some time in Afghanistan last year, and you look at what it takes for them to prepare for a mission, to execute a mission. They are pulling data from a variety of sources, some unclassified, some classified.”

But doing that today is damnably hard. It takes a lot of awkward workarounds to bridge the gaps between different and frequently incompatible networks, and you can't bring the kludged-together solution with you into combat. That's why one of JEDI's first priorities is building backpack-sized mini-servers.

“To actually combine that data and physically get the information out to the warfighter in a form factor that they could use when they're out in the field, it just doesn't exist today. And no — you cannot pull that off the shelf,” Deasy said. “That is a unique capability that we have to build.”

“We have to find a partner to help us do that, and that is what we've been looking to do with JEDI,” he told me. He really means a partner, one contractor, not many, because the task of building this highly complex, tightly integrated system is not something you can split up, the way you would an order for bulk commodities like potatoes, jet fuel, or even online storage.

Why not? Let's let Deasy explain it in his own words (edited for clarity and brevity).

Q: There's been a lot of excitement over JEDI since the program began in 2018, and a lot of frustration over the delays. How would you respond to the critics who say it's time to give up, or even that it was the wrong approach all along?

A: At the time I joined [the Defense Department], which was actually two years ago this week, the first thing that Deputy Shanahan turned over to me was JEDI. The first thing he asked me to do was to go back and take a hard look at was, was this the right thing we were doing for the Department of Defense, were we going about it the right way.

Was it the right thing? Yes. Were we going about the right way? Well, I'd say, mixed results.

[Now] there's this whole conversation: “Should the DoD give up? Should the DoD start over? Should the DoD go and do something else?” I've spent a lot of time contemplating a bunch of different scenarios, and no matter what scenario I look at, you still have to solve the problem for the warfighter. We need to take data all the way out to the tactical edge, across multiple classification levels.

And even if I wanted to stop JEDI today, there is no solution that is available already inside the Department of Defense to do that. I'd have to turn right around, go back out to the market, start an RFP once again to solve for that particular problem.

This is why we stay the course.

We're not staying the course because we're just being defiant or stubborn. We're staying the course because it's the shortest way to get from point A to point B, because if we don't stay this course, we will still have to go back and solve this particular warfighting need. And that is why I believe staying with JEDI and moving forward is the right solution.

It's very easy for critics to say, “hey, there's a bunch of clouds already inside of the Department of Defense, why don't you just go use one of those?” Or “why don't you just split this up and give this to a bunch of different suppliers?”

Yes, of course, JEDI can do commodity cloud capabilities, and so do a lot of our other clouds across the Department of Defense. The whole world of commodity cloud has gotten better and better. But it doesn't solve for our classification levels. It doesn't solve for the tactical edge today.

If you look at the heart of that RFP [the 2018 Request For Proposals] and you really sort through all the requirements, what makes JEDI still unique today, that cannot be satisfied by other cloud environments, is the fact that it was solving for both OCONUS [Outside the Continental United States] and CONUS; it's moving data across multiple classification levels; and it was looking to create a commercial solution that would give us far better terms, conditions, and pricing than we'd ever seen inside the Department of Defense.

When we looked across the landscape of all the cloud environments we had, there was not a single cloud environment that we had that could do all those things, nor was there one being contemplated inside the Department of Defense.

We've got the Army that is now looking to consolidate their clouds, we have the Air Force has their cloudOne platform, Navy has stood up a special purpose cloud with their SAP HANA to consolidate their various SAP environments. All of those things fit exactly what we were trying to achieve in the cloud strategy document at the end of 2018.

However, if you look at all those cloud environments and other ones that are stood up across Department of Defense, none of those, still, can do CONUS and OCONUS, none of them is solving for the tactical edge, and none of them is solving for multiple classification levels.

[Before the stop-work order], we had dozens of projects across combatant commands and the services wanting to be the first to standup in the new JEDI cloud, because of two fundamental things: It offered capabilities that their clouds didn't offer and it offered it at a way better price.

At the end of the day, the most competitive way of looking at market forces is, where are the services going to? And they were clearly going towards JEDI because of what it offered in terms of technology and what it offered in terms of price.

One of the criteria that we really wanted out of JEDI was to get to the best commercial terms and conditions. And I can tell you after we were done with that award, we clearly in that award had better terms, better pricing than we had in any cloud across the Department.

Q: But you took a long time assessing which competitors could meet your technical requirements, finally choosing Microsoft. Given the delays, and given how fast IT changes, is that assessment now obsolete?

A: We did not take this final decision on the selection of our vendor until towards the back half of last year. Yes, we started this in 2018, but the offerings that we were looking at were being updated and refreshed throughout the entire RFP process until the point that they submitted their final submissions.

Our [implementation] schedule is actually going to be in phases. First, we're going to roll out unclassified, then we're going to roll out the secret, and then we're going to roll out the top secret. And those solutions were going to be designed and built as we went through this process. One of the reasons we did that was because we did recognize that technology would change.

We set it up in a way that we absolutely can stay fresh with technology as it changes, because we have these option periods [at two years, five years, and eight years] to go back and look at whoever our provider is and to decide whether or not they're staying current.

If we saw that a vendor was starting to lose its competitiveness either on pricing, on speed of delivery, or on technology, you make it clear that if they were to continue down the path they're going, there's not going to be a renewal.

The best evidence you get is just how are they delivering every day? Is it working, is it up and running? Do they really give you a tactical edge? Do they really give you multiple classifications? Are the warfighters benefiting from it?

Q: But why is having a single contractor you can opt out of at set times better than having multiple vendors competing all the time for work orders under an Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quanity contract?

A: It's a fair question. And if what we were providing the Department of Defense was pure commodity cloud, a platform for storing and compute and building applications in a standard way that we see industry doing it today, IDIQ would be a perfect way to go.

But that's not what we're doing here. That's what gets lost in this whole conversation. This is not your typical, basic, commodity cloud offering where you can put it out to three or four vendors and let the service pick every day who they want.

Let's go back to what the requirements are. We are trying to build a cloud that can handle CONUS, OCONUS, unclassified, secret, top secret, traverse the data between those environments, and create hardware solutions at forward bases and to the tactical edge.

Imagine for a second that I now wanted to have three or four vendors to do that. Think of the complexity it would take to build cross domain solutions for unclassified, top secret and secret, OCONUS, CONUS, forward bases, tactical edge devices, all the way out to the guys on the side of the mountain.

Especially when you think about trying to move forward with this Joint All-Domain Command & Control, where the fight of the future is going to be multiple services and combatant commands having to work together and share data. That becomes almost untenable if you set it up as an IDIQ with multiple vendors. I mean, how would you ever build that to work all the way to the tactical edge?

To move data from unclassified to secret to top secret, it's extremely complicated. It's not like you go buy this off the shelf. This is a very bespoke, tailored solution that has to be built.

There is an actual hardware element of this, of creating the hardened devices that need to be put into the hands of a warfighter out there on a mission and that's what we don't have today. You have to find a vendor that can help you build those hardened devices out on the tactical edge.

If we're doing IDIQs and every time we have a new warfighter need, we now are going to go out for three or four vendors, we're going to put that out, they're going to come back and bid, they're going to give a solution and then we have to go back and now re-integrate that solution. That gets be very hard and very complicated and very time consuming.

You have to FEDRAMP all of them, you have to test all of them, you got to run them through certification. We have to put NSA red teams onto them, we have to put US Cyber Command to oversee each of those environments. Is that in the taxpayer's best interest? Does that sound like to you the lowest cost, most efficient solution for the DoD and the warfighter?

There's going to be a lot of business across the Department of Defense where IDIQs are going to be perfect and we'll have lots of cloud providers that will flourish. But JEDI is a unique environment where having a partner to help us build this out is the smartest way to go.

Throughout this entire process one thing has stayed constant: You have to find a way of putting a warfighter cloud capability into the hands of our men and women out on the tactical edge every day. And I've always looked at my responsibilities as CIO is to not to satisfy the cloud industry, but to satisfy what the warfighter needs. We have a unique war-fighting need that you just can't go get off of the shelf today.

https://breakingdefense.com/2020/05/exclusive-dods-cio-makes-case-for-sticking-with-jedi